Towards a Theory of Transformation of the INGO Operating Model

Tim Boyes-Watson

July 27, 2023

The stand-out pledge that these world leaders made as they launched the Grand Bargain on 24 May 2016 at the World Humanitarian Summit in Istanbul was to ensure that “Local actors would receive 25% of all humanitarian assistance funding by 2020, as directly as possible”.

This wasn’t a new idea, and indeed many NGOs had been working towards what some called a participation revolution for decades. Six years before, in 2010, Raj Shah the Administrator of USAID committed to direct 30% of USAID Mission program funds to local entities by 2015. And USAID did manage to increase the proportion from 9.7% in 2010 to 18.6% in 2015. The most recently appointed USAID Administrator, Samantha Power, has made a wider pledge to increase the proportion of all USAID funding, (not just via Missions), that is going to local entities to 25% by 2025. The latest progress report for financial year 2022 shows that this proportion is now 10.2% and that the proportion of USAID Mission funds that is going to local entities is ‘back’ to the 18% level that was reached in 2015.

However, Samantha Power, has admitted that their 25% goal will be very hard to reach. The Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2023 published by Development Initiatives reported that the proportion of overall international humanitarian assistance directly provided to local and national actors in 2022 was just 1.2%, (US$485 million), and had not increased at all since the year before. Looking back to when I first used this photo of mine in a blog in 2017, the direct funding of local actors has crept up from 0.2% in 2015. Some progress is being made but it is painfully slow.

In 2014, when I first met Degan Ali, a key figure in securing the 25% Grand Bargain commitment, she impressed on me that we need to dismantle systemic barriers to localisation, such as the lack of international standards and harmonisation in areas such as NGO financial reporting, due diligence and provision of indirect or overhead costs. At that time, I was CEO of Mango, and we made these our key long-term strategic objectives. They were a big driver of Mango’s merger with InsideNGO and LINGOs to create Humentum. Humentum’s subsequent partnership with CIPFA has made tremendous progress towards creating the first ever global accounting standard for the non-profit sector through IFR4NPO. I still work closely with Humentum and IFR4NPO on these initiatives.

When we co-created Fair Funding Solutions we committed to contributing to these same systems change objectives, so that we can move to a fair funding future where:

- Project grants cover their full costs

- A single audit of each non-profit meets the needs of all their funders

- Non-profits and funders passport due diligence.

I continue to be inspired by Degan’s advice and believe that these systems change initiatives will make a big difference to creating an enabling environment for localisation, or locally-led development. However, I also recognise that they will be far from sufficient in catalysing the much wider and deeper transformation that is needed.

What I have understood from Degan Ali and other thought leaders like Themrise Khan is that for transformation to happen, then it will need to be southern-led. Degan is leading by doing and has convened the Pledge for Change for INGOs. The Pledge requires accountability on familiar targets around funding for local partners, overhead costs and harmonising due diligence. And it goes well beyond these to reimagine the role of INGOs, which will require them to transform how they are structured and work – their operating model.

Emerging learning from our consulting with INGOs who are seeking transformation

Fair Funding Solutions’ other key areas of work are consulting and coaching, which catalyses and sustains organisational transformation. We are currently advising three INGO clients that are each on their own unique journeys of transformation towards supporting more locally led or participative development.

They differ from each other in terms of programme focus and are starting at different points along this transformation journey. While the differences between these clients mean that the advice and co-creation we are doing with them is bespoke and contextualised, comparing and contrasting our analysis of their transformations is starting to build new insights for us on what it might take to transform an INGO.

What we have also discovered, is that despite many years of talking about the transformation needed to the role of INGOs, that there are relatively few who are really ‘walking the talk’ yet. It seems there are big barriers to really getting started on this journey, and that there are a lot of cultural and systemic forces that mean that this sort of transformation initially brings high levels of internal and external resistance.

So what does it really take to shift the INGO Operating Model?

The other key area of learning that is emerging from our work is about the changes that INGOs need to make to change their operating model and what might help or hinder that.

I’ve already co-written with my ADD colleagues about the “Price of Transformation” that is being exacted from them as they seek to change their funding and financing model.

What we are now starting to build is a theory of the INGO Operating Model needed to support the transformation. The structure of this was inspired and informed by Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors work on “Operating Archetypes” that form a central part of their “Theory of the Foundation”.

We have so far developed 5 common ‘Operating Models’ for INGOs, see table below. In practice, we are finding that few INGOs seek to specialise and focus all their energy and resources on just one of these Operating Models. That has often been for good reason, as for many years INGOs have pursued theories of change that combine a portfolio of work at different levels and have different modalities. One of the key questions we are working through with clients will be whether there are significant advantages in seeking to pursue a narrower range of Operating Models as part of the process of transformation.

| Operating Model | |||||

| Characteristics of the Operating Model | Implementers | Intermediaries | Participatory Grant-makers | Facilitators | Advocates |

| Description | Implement projects according to plans and budgets that have been agreed with the relevant funders. | Making grants to partners, that then implement projects according to plans and budgets that have been agreed with the relevant funders. | Making mostly unrestricted or highly flexible grants to partners to address priorities that have been identified by the communities involved. | Facilitate and broker partnerships and access to funding. May involve providing training and support to partners. | Carry out research, policy development and advocacy. |

| Location | Highly autonomous operational units located where programmes are being delivered. | Less autonomous operational units that can increasingly be serviced by regional or global service centres. | Likely only to need regional or global service centres. | ||

| Physical offices | Yes | Probably | Not necessarily | ||

| Transaction volume | High | Medium | Low | Low-Medium | Low |

| Key Cost Drivers | Large volumes of goods and services inviolved in programme delivery. Salaries, office costs and travel. | Mainly restricted grants, salaries and travel, but may involve some procurement and delivery of activities for, or with, partners. | Mainly unrestricted and salaries of staff involved in grant-making and partner accompaniment. | Mainly salaries. May also use contractors and/or partners to provide training, consulting and convening services. | Mainly salaries. May also use contractors and/or partners to carry out research and policy development. |

| Spend on compliance | High | High | Medium | Low | Low |

I have compared this emerging categorisation of INGO operating models with similar attempts to analyse cost data by organisational type in previous research that I was involved with, carried out by Mango, Bond, InsideNGO and Humentum.

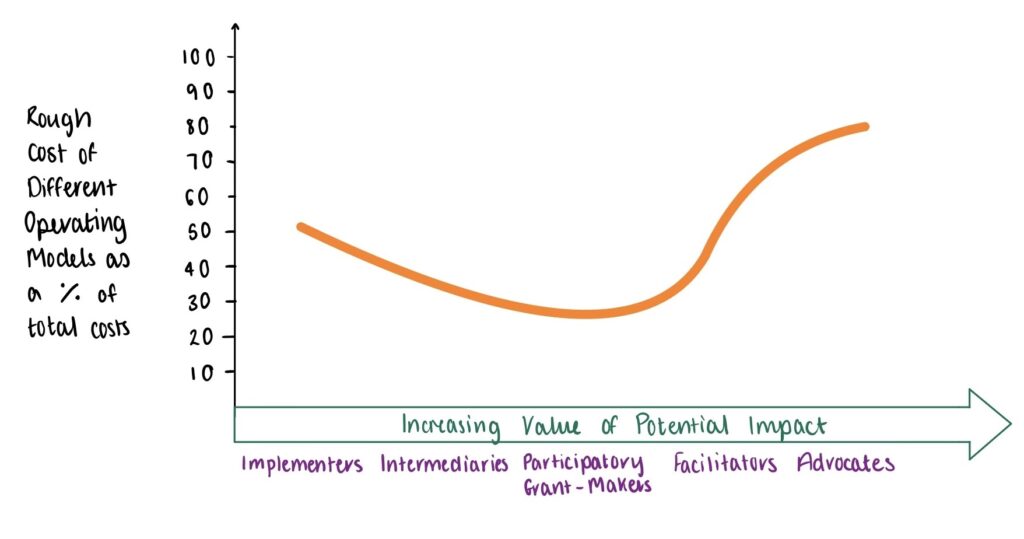

What is emerging is a hypothesis which I sketch below.

I emphasise this is an illustrative sketch and huge caveats are needed when looking at the estimates we have made in the graph, before you apply them in anyway as a benchmark to any other organisation.

The methodology we have employed in making estimates around ‘typical’ cost structures for different Operating Models is based on this previous cost data analysis that cannot in anyway be described as robust. All previous work analysing cost data, based on a typology of similar Operating Models, showed that the range of data points in any given Operating Model type tended to be high.

The same caveats need to be applied to the judgements we have made about the level of potential impact of these different operating models. These are drawn from previous work I have done on Value for Money with Bond and others.

That said, if this hypothesis is valid, it could go some way to explaining some of the challenges for any INGO that is seeking to shift its dominant Operating Models towards the right of this diagram.

If you are currently an international Implementer, seeking to become more of an Intermediary and provide a much greater proportion of your income as grants to local partners, you are likely to need to dismantle a fair proportion of your existing country infrastructure, move some of it to regional or global service centres and reduce the relative cost of your Operating Model.

Whereas if you are already an Intermediary that receives institutional donor funding, but delivers through local partners and are now seeking to move to being a Participatory Grant-Maker, your road map is different. You are probably going to need to attract more unrestricted sources of funding, dismantle any country-based infrastructure you built to provide capacity strengthening and monitoring, and repurpose your programme support infrastructure to become partner accompaniment. This requires a very different mindset. You will also probably need to move to a lower relative cost of your Operating Model.

If you are INGO that is trying to shift your dominant Operating Model to either of the two right-hand categories, you hit a quantum leap in the difficulties you will face in financing the apparent rising relative cost of your Operating Model. While the absolute cost of these Operating Models is likely to be lower than those on the left-hand side, these costs appear relatively high because they are not being diluted by large grants flowing through the INGO. Therefore, although such INGOs might be doing impactful work brokering partnerships or becoming a sub-recipient to local partners – there will be massive challenges in scraping enough resources to fund this Operating Model from the poor cost coverage that most donors give to sub-recipients.

INGOs that move into two most right-hand Operating Models and become sub-recipients will be likely to face the same cost-squeeze that has been highlighted in Development Initiatives research on the provision of overheads to local and national partners. However, now the role of Intermediary may well be played by a national NGO, rather than an INGO.

Conclusions and Next Steps – Join the Conversation on 14 September 2023, 15:00 UK Time

I hope we have made it abundantly clear, that the emerging learning we are gathering from our work with INGOs that are seeking transformation is just that – emerging. It may not be representative or generalisable. However, as this is sadly still such a new area of work it needs discussion and we want to share everything we are learning as we go. Fair Funding Solutions is committed to co-creating ideas and sharing knowledge as widely as possible.

We invite you to join us in sharing your challenges and learning about the transformation of INGOs and of the development and humanitarian ‘industry’. Please come to a FREE online conversation about Transforming the INGO Operating Model on 14 September 2023, 15:00 UK Time and/or join our mailing list here.